Getting in touch with the power that drives the Universe...

Every year around August I start thinking about the bombs.

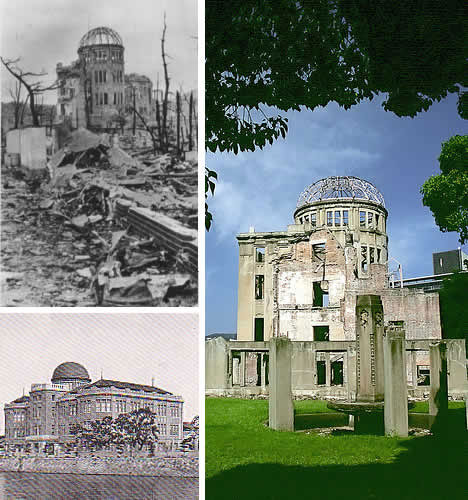

In 2004 during my first teacher exchange program with Japan, I was able to visit the site of the first nuclear bomb attack in history. The national museum in Hiroshima is set up to take you on an increasingly sensitive journey through the historical, scientific and personal aspects of the bomb that fell on August 6th, 1945.

In the ultimate gallery I was able to view a rusty, broken tricycle that had been buried with its owner, a 4-year-old boy, in the yard of the family home after he had died of radiation exposure. At the time of his death the family’s pain had been too intense to share publicly. Many years later the boy’s father had decided to donate it to the museum in order to honor his son’s memory. I had never experienced such a profound, sensitive tribute to a person in my own country.

The next year I was fortunate to become an adjunct faculty member of a junior high school in Daizafu-shi, Fukuoka, Japan for an entire summer session. I fully engaged the junior high students at the school. I felt a special kinship with them. I greeted them each day alongside the principal and got to know their teachers closely in their faculty lounge. Deep friendships were developed. Using translators, I taught lessons in various subject disciplines and got to know students in their club and social activities. Even though I did not speak their language, we could "read" each other’s actions and faces. There was a special bond among us.

Perhaps the most memorable activity of that period was a yearly school assembly to commemorate the culturally significant death of a young teenage girl due to the circumstances of her radiation poisoning after the Nagasaki nuclear bomb was dropped in August, 1945. The story had been immortalized through a popular, poignant book that was well known to the students and staff. The assembly that day included a slide show of the book’s illustrations and a student-led recitation of the content. A few students even offered their personal perspectives about the book. Including my previous observations in Hiroshima, I continued to think about the ramifications of being in a culture on the losing-end of a major war. The mood was somber and reflective. Even though the ceremony was conducted in Japanese language, I could sense the sadness and loss of students and teachers relating to a peer that had died decades before any of them lived. I was able to follow along in an English translation of the book as I quietly observed.

As I sat in this auditorium of perhaps 500 Japanese adults and teens, it crushed me to know that I was the sole representative of the nation who had been the victor over them, and directly contributed to the death of this young girl. It was perhaps the loneliest moment I will ever experience. I wanted to apologize and ease their pain, but as someone who was born after the bombings, how could I?

Later that summer, I visited the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum with one of my host Japanese teacher colleagues. Sensei (teacher) Arata Matsumoto was a perfect philosophical guide through the Nagasaki museum and memorials, although he could not bring himself to enter the museum with me. He was so very able to personalize the experience and attach my general knowledge to a specific life. He related his own junior high experience of visiting the museum and for the first time in his life learning about the tragedy that his nation had suffered. He’d left his school group for quite some time to regain his composure. He was devastated to learn about the pain his countrymen and family had experienced. His perspective on his life and country was forever changed.

As a scientist and history buff, I was aware of the technical aspects of the nuclear bomb attacks upon Japan. As a veteran, I knew about our difficult war experience with that country. But I had never had the privilege of learning about the personal effects of the bombs until I visited Japan and got to know some Japanese intimately. The trips to the bomb museums gave me a much-needed and re-calibrated perspective about the human experience of the bombs and war in general. At this time my own first grandchild had been born and this searing memory of a child’s painful death caused me anguish. I thought “How would I respond if this had happened to my own children or grandchildren?"

How does one individual begin to apologize for a clash of cultures and civilizations? For monumental cultural sins and misunderstandings? Currently in our country the issue of financial reparations for persons of Black heritage is being discussed. Perhaps it will happen; perhaps not. But my question which has not yet been answered is: What kind of reparations can be made for damages that have stained history so indelibly that the damage can never be undone? Never truly forgotten and put behind us? To my knowledge, the only “reparation” that has ever been completely successful is the Cross. But it, like all reparations, can be rejected or misused. Where do I stand as a Christian member of a culture making reparations for historical evils that I did not participate in or personally embrace? Can money or other material resources erase centuries of inhumane treatment and social evil? I wonder if the answer is moving forward and acting in loving, sacrificial relationship rather than looking back and trying to erase horrors that aren’t erasable.

I think the answer must lie at least partly in the level of our own individual participation in such an apology. If we expect impersonal government actions or material payments to eliminate feelings of prejudice and bigotry, we are probably kidding ourselves. Maybe it’s necessary that a national apology be delivered person-by-person, heart-to-heart, moment-by-moment. It seems to me that some evils are not “undoable” from a human perspective; we can only move forward and create a new culture in which bigotry and prejudice have no place. Philip Yancey wrote in What’s So Amazing About Grace that “Evil is overcome by good only if the injured party absorbs it, refusing to allow it to go any further.” Clearly there were/are specific victims of the nuclear bombs, racial prejudice, misogyny and other cultural evils. But when cultures go bad, everyone suffers to some extent. It’s not a problem that some mythical “they” will solve; it’s everyone’s problem. And it will only be solved to the extent that we all get involved in the solution.

Just today I briefly read a summary statement of the Bible patriarch Joseph’s life experience. It was quite unexpected but noteworthy. Speaking in Joseph’s voice, it said “You sold me into slavery, but God sent me.” Joseph was speaking to his brothers who had jealously sold him into slavery to punish him for their father’s favoritism of him. Joseph, though bent by years of imprisonment, slavery and wrongdoing, was unbroken. Actually, it made him a better person than he otherwise would have been. His perspective changed from vengefulness to thankfulness. He realized that all along, God had been allowing him to live through adversity, only to become stronger, better, more God-focused, more thankful, more grace-giving, more Christ-like! If there was anyone in the Bible who deserved reparations, Joseph would be at the top of the list. But for Joseph, reparations involved healing relationships with his brothers and blessing them in exchange for their maltreatment. He returned good for evil. He allowed evil to go no further.

Perhaps that is what Jesus was trying to show us. He, himself, became the reparation for what sin had done to mankind. He was the ransom. The kinsman who redeemed us. Reparations are personal. They’re costly. They're especially time-consuming. They begin with the next person we meet. They don’t look back. They are truly freeing. They are an all-important “do over.” But like love and bread, they must be made new and fresh each day.

Bless you as you do your part to become a living reparation for Christ’s sake.

Views: 7

- Attachments:

© 2025 Created by Brad Fox.

Powered by

![]()